Viola’s crossdressing in

Twelfth Night is one of the more unique crossdressing narratives in

existence, if you ask me. It has a unique attribute that sets it apart not only

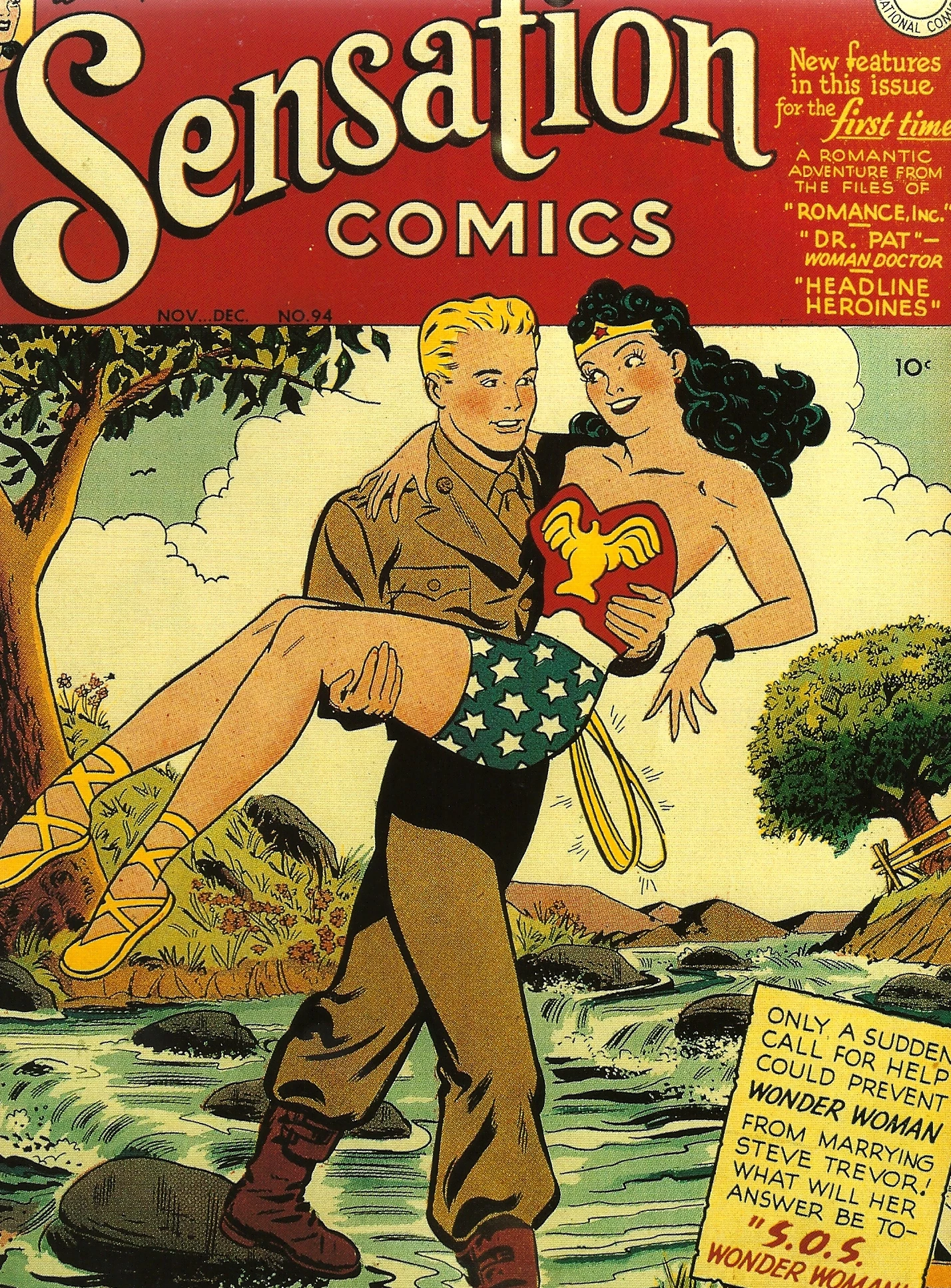

from other stories, but even from its own adaptations, at times. Even in movies

like She’s the Man, directly based

off Twelfth Night, the crossdressing involved has a significant difference at

hand: it’s fully intentional.

In She’s the Man,

Viola wants to play soccer, so her choice to switch with her brother is a

specifically chosen act. In Disney’s Motocrossed,

loosely based on Twelfth Night,

Andrea (the Viola character) takes her brother’s place in the race. In other

Shakespeare tales, such as The Merchant

of Venice and As You Like It, the

audience is given the impression that the crossdressing can be undone at any

time. Portia in The Merchant of Venice hopes

to fix Bassanio’s debt to Antonio, ensuring the safety of her marriage. Rosalind

in As You Like It maintains her

disguise to continue wooing Orlando.

Yet, in Twelfth Night,

none of that flexibility seems to be present. Sure, Viola makes the choice

to dress as Cesario, but it’s not out of any personal benefit. It’s for the

sake of her safety. In Illyria there are only two great powers, Orsino and Olivia,

and Olivia is grieving and won’t take new staff. Orsino, on the other hand,

will likely only accept a man, or at least, Viola doesn’t seem to feel like going

into his service as a woman.

Then Viola, as Cesario, woos Olivia for Orsino – but it

backfires. Olivia falls for her instead. And Viola then reaffirms the idea that

she is crossdressing mainly because she has to, not because she wants to,

because of how much she seems to regret that Olivia has been tricked. “Poor

lady, she would better love a dream,” she says, mourning Olivia’s unluckiness

in falling for her. She also mentions that “time” must untangle this problem,

because “it is too hard a knot for me to untie!” Viola feels that there is

nothing she can do about Olivia’s doomed love.

|

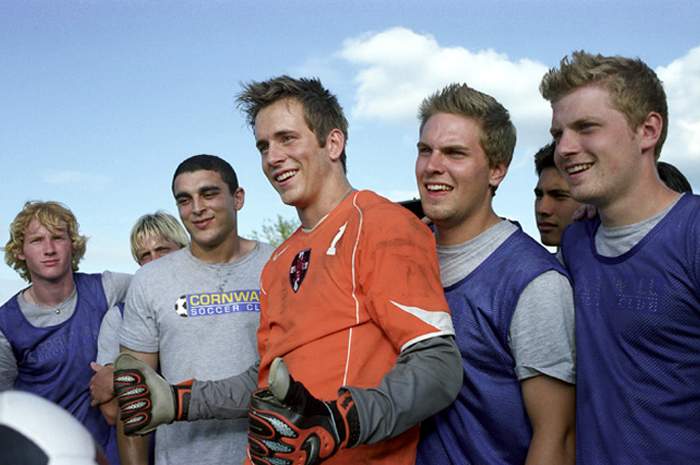

| "Arry" with Gendry, a fellow recuit, among other things. |

The only other instance I can think of where a female character crossdresses out of necessity, not opportunity, might be something like Arya’s situation in Game of Thrones and A Song of Ice and Fire. At one point early in the story, when her family is in trouble, Arya is forced to flee for her life. She joins up with some Night’s Watch recruits, but in order to do so safely, she dresses as a boy and takes on the name “Arry.” A few interesting incidents come up as a result of her disguise. At times, Arya shows frustration with her disguise, similarly to Viola in her position in Twelfth Night.

Perhaps it’s just that these situations are more difficult

to write and deal with, but it’s still interesting how crossdressing women in fiction

usually seem to have some degree of agency in their crossdressing, and to point

out the exceptions to that guideline. I would argue that it often paints a more

sympathetic picture of the crossdresser in question – fiction often demonizes

women being selfish and taking action, or pursuing “usurp’d” masculinity, so a

woman forced into those situations, rather than choosing them, becomes more

palatable to a generally sexist audience.